Like a lot of my blog posts here, this one was sparked at a specific time over a specific conversation, but over the years I’ve seen this particular topic come up again and again like waves on a shore, so I’ll often point back to it, rather than hashing out the same things I’ve already said over and over again. Part of the Queer Experience ™ is that whole exhaustion over having to have the same 101 (or more complicated) discussion over, and over, and over. So, if you find I’ve aimed a link back here, and you find yourself maybe thinking ‘Wait, this is from X years ago!’ and wondering why? That’s why.

***

One of the things about being a queer author of short fiction that usually finds itself on the more spec fic side of the street than the romantic is I’m not often a part of the romance culture as I’d like to be. I love romance, and a great deal of the short fiction I’ve written has definitely been gay romance, and even my first novel, Light, had a romantic sub-plot that was almost as weighty to the sum total of the book as the spec fic content was. I do write romance novellas (three so far!) but I’m often removed from the discussions by a step or two.

Often, this means I don’t often see a lot of the discussions that occur until they’re very well underway, and often those discussions have turned into a lot of anger before I see them at all. Which sort of sucks. I often only see a topic when someone posts a “This is So Damn Wrong!” post, a “It’s No Big Deal!” post, or a “What is Wrong With Everyone?” post.

Romance is a great place, and I have to believe that the hot tempers come from a place of passion for romance to be a force for good. When people feel strongly about something, they react strongly, too. That’s an awesome thing that can also turn a bit sideways. It’s also very, very easy to feel that anything that criticizes something you’re passionate about is an attack on the thing you’re passionate about.

Real criticism isn’t that.

Whether talking about the potential for male pseudonyms to be appropriative in the m/m writing world, or the firmly entrenched systematic racism on display when someone declares they have lines for black and latin romances, and thereby don’t look at those for the main imprints, or someone points out there are major missteps with the author’s representation of native culture, it can be uncomfortable and awkward to stop and say, “Wait. It’s possible something I care about is doing harm.” While I can understand it’s a natural reaction to think, “I don’t feel any ill will to people who are X, and this feels like someone is accusing me of acting negatively to people who are X!” what is really being said is: “this story/process/system is hurtful/stigmatizing/ignoring/erasing/restricting to X.”

So.

Gay-for-you. (Or, alternatively, out-for-you.)

I almost didn’t write this post. Like the post I wrote last year on pseudonyms, I’m a little bit worried about how this could go, honestly. But the pseudonym post went well and people were polite, so here we go.

That trope of Gay-for-you.

Wow, what a mess. Again, I walked into this late, and maybe I missed some of the more moderate discussions that may have taken place, but I’m mostly seeing angry from both sides, or dismissiveness from both sides. And I will say both sides can and indeed do have points that are valid.

Now, I’ve said before I find gay-for-you plots somewhat problematic. Coming at it from a few different angles, here, there are multiple factors that make me flinch. But the first one that I’ve seen a few times is the very dismissive “Gay-for-you is just a trope, like millionaires or big misunderstandings.”

Being queer is not on par with a career or a social misunderstanding. I get what is intended by what’s being said: that this is romance, and themes and plotlines recur in romance, and that this theme: the straight guy who falls for another guy, is a plotline, but saying that it’s a trope is insulting to those of us who’ve lived a queer life (and, often, suffered for doing so) when you’re equating it with the life of a fictional millionaire, or a guy and a gal who just need to stop for five minutes and talk to solve their problems. Unlike that fictional millionaire or a conversation, queerdom is an identity and a minority with a history of being stomped down on. How you portray a member of a living, breathing culture of people is important. And if you do it wrong—in ignorance or on purpose—it can’t surprise you to hear about it.

Like I said, I do understand what was intended by the sentiment: the goal of the gay-for-you story is to provide entertainment and deliver a romantic story for the enjoyment of the reader. And there’s an odd sense that a gay-for-you story can’t do that and still be harmful or painful to queer readers. It totally can. People have enjoyed and loved on things that are reductive or erasing or stigmatizing before, and they’ll do it again. Look at Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

So, no. We queerfolk? Not just a trope.

The incredible vanishing bisexual…

Next, there’s the notion of erasure. Now, most people talk about bi erasure, and I absolutely agree on that point, but I’ll expand a little. I’ve read more than a few stories where the plot of a gay-for-you story never even mentions the word bisexual, and every time it sets my teeth on edge. Straight and Gay (or Lesbian) are labels, and I see a lot of well-meaning people say things like “labels are so reductive” and “we need to move past labels” and “why do we have to label something that means love in the first place”? On the surface, those sound like completely valid statements. I even found myself wondering why it bothered me at first.

But after some thought, it comes to this:

You’ve probably heard of the campaign Silence = Death. That label I see declared unnecessary and shrugged out of existence in the name of love and romance and puppies? That label: gay? (Or bi, or pan, or demi, or ace, or queer, or trans or…?)

It matters.

It matters and has impact in my life all the time. It is absolutely a part of who I am. It’s not everything, no, but it’s a major thing and some times and in some situations it’s the most central thing. Queerfolk have to fight for the right to be queer. To not be tossed in camps, or jails, or beaten to death, or denied marriage, or any number of other things. That’s not finished.

Not saying the words is a form of erasure, period, and it absolutely feeds into the shame and tells those who feel those things shouldn’t be talked about that they’re right. In my life, I have heard so many variations of this.

“Oh, I don’t care what you do in your bedroom, but I don’t want to see it.”

“I just wish you didn’t call it marriage.”

“I don’t know why you have to declare yourselves so much.”

What’s really being said there is “I’d rather you go away.”

I get that it would be lovely to live in a world where labels don’t matter, but the reality is we’re not there yet, I’m not sure we ever will be, and in the mean time? They do. And for bi folk? They get crap from both within and without. Someone who is gay can (and often does) have very different experiences than someone who is bisexual or pansexual, and that matters. The identity, the label, the word. It matters.

It’s how we find each other. It’s how we create our logical families if our biological families slam the door. It’s how we find a sense of who we are.

Words are tools. Labels are, too. And not just the sexuality ones. My husband is exactly that—my husband—and that title (or label) has impact and power from a legal, cultural, and sociological point of view. So does gay, or straight, or bisexual, or pansexual, or lesbian, or transgender, or…

Well, you get my point.

So when an author decides that there’s no point in even dropping the word “bisexual” or “pansexual” into a narrative (or that it’s not important at all), and that a character who is almost entirely attracted to people of a different gender finds someone who matches their gender and they fall in love, and the character continues to self-declare as straight and there are no societal ripples in the narrative at all, it grinds me to a halt and breaks verisimilitude.

This comes up in the queer community quite a bit, where bi erasure is a struggle as well. A bisexual man who is in a relationship with a woman doesn’t become straight by virtue of their pairing. He is still bisexual. If he dates a man, he doesn’t become gay. He is still bisexual. Ditto pansexual folk. I’ve had bi friends reduced to tears when people shrug off their identity because “it’s easier just to think of you as gay” or “well, you’re mostly with men, so I figure you’re straight now” or “whatever, sexuality is a spectrum.” When a story presents a fictional character that reinforces this “he’s straight (or she’s straight) but with another man (or woman)” dismissal, it’s reinforcing something that’s already a problem.

I get that this is romance, and I get that romance is happily-ever-after (or for-now), but as a reader—and as a queer guy—at best I give up on the story, and at worst I can’t help but consider that the author isn’t particularly well informed in queer culture or is actively deciding a sensitive or accurate portrayal of queer culture doesn’t really matter. I love reading stories where queer folk find loving families, acceptance, and love. That story isn’t told anywhere near as often as it should be. Many gay-for-you stories have the perfect set-up for that sort of story, but skip it completely because, hey, it’s just hot if he’s straight.

Y’know, except for with that one guy.

Another side of erasure to consider here may sound a bit silly, but the straight half of the gay-for-you coupling also kind of gets to erase the whole growing-up-queer factor that is a reality for those of us who did exactly that. Coming out (and one of the reasons I certainly think “Out for You” is a better term for what regardless remains a wonky trope if it’s still written as a straight guy finding that one other guy to be with) is way, way more than just “Oh, so it turns out I’m turned on by you. Neat.” And to be fair, in many of the gay-for-you stories I’ve read, the straight fellow in question does seem to struggle most of the time with what it might mean, but this is where those darn labels come in handy in the real-world coming out process.

Because it takes language to work out these things.

I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve read a gay-for-you story and the straight character’s thought processes are, “This makes no sense. I know I’m not gay. I can’t be gay! I like sex with women. What the hell is going on?” I want to scream the word “bisexual!” at the book.

My tween niece has more functional ability to categorize and process the sexuality spectrum than these characters, and it’s painful.

Imagine a bi reader with that story. Everything about that moment is right there as an opportunity for the character to invite the reader in and stand in front of a mirror. Instead, the author draws curtains and closes and locks the front door.

But no, I think it’s sexy!

Now, the idea that gay-for-you can be harmful when the people writing and reading the books are themselves totally into the sex being displayed can also seem counterintuitive. One blog I read pointed out that opponents of gay-for-you were basically attacking their allies.

It’s perfectly possible to do damage as an ally. Seriously. And one of the biggest and easiest mistakes to make is to talk when it’s time to listen. As a guy, I want to be the best feminist I can. Being queer gives me a slice of insight into what it’s like to be shoved down for something that shouldn’t matter. But I’m still a guy. I still grew up with access to all the privileges that come with being a man. The biggest and best thing I can do as a feminist is to listen when women tell me about an issue, and then try to boost their voices on the topic as well as change my own behaviour. Now, when I’m in a male environment and there are no women around, and someone says some sexist shit, I’ll call it out. But when I’m in an environment where a woman is speaking to a topic and providing that point of view, my job is to shut up and listen.

That’s a huge part of being an ally. So if you’re a queer ally and you’re taking part in something that a lot of queer people point out isn’t queer-positive?

It’s time to listen.

It’s sexier, because, y’know, straight guys…

The whole “straight-acting” masculine thing? Can be toxic. I explored that a bit in “Shutout.”

Let’s unpack a bit why it’s important the character be straight, rather than closeted, or just unaware of their (as yet unexplored and unimagined, or rarely same-gender aligned) bisexuality or pansexuality. Why is that, exactly? I mean, I know I’m stepping into the great unknowable that is desire and what gets folks hot, but there’s something a bit off, here.

Now, there’s the absolutely, well-documented notion of situational homosexual acts. Guys in jail is probably the short-hand. But that’s not what’s being done with a gay-for-you story, right? No, in a gay-for-you story, the straight man discovers actual romantic and erotic feelings for a particular other guy, and then, ultimately, sex and relationships ensue. No one gets out of jail and reverts back to their previous self-declared state. The straight man is now with the other guy, and they are together.

So…why is this sexier than a guy who, when the same scenario starts to unfold, has a moment—which could absolutely still include panic and worry and all the other freak-out moments that come with coming-out—where he thinks, Oh man. I might be bi. Or has a friend say, “Dude, it’s okay. You could be pan or bi. And hey, if you are, I’ve got your back.” Or any number of other easy-to-include-non-erasure-and-far-more-reflective-of-reality options?

I can’t quite help but feel it plays into a sense of masculinity that is not being ascribed to a gay guy (or a bi guy, or any form of a queer guy). Like, somehow, it’s just hotter if he’s straight and he still gets it on with another guy. Because gay stuff, or bi stuff? Not as hot.

And by “not as hot” what I see is “not as good as” or “less worth” or any which way you’d like to translate what amounts to just another version of the same old garbage we spit out about how men are men, and what masculinity is…and definitely isn’t.

It feels like, “I want to get off on watching two guys, but I totally don’t want them to be, like, actually gay or anything.”

There is so much damage done by the notion of “straight-acting” in the queer male community. Gay-for-you plays right into that pile of crap.

Or, put another way, if you’re claiming it doesn’t matter what label is used, why not use the label that would be more inclusive and create visibility? Why actively not do something that would by your own admission be a good thing?

Well, if you just found the right one…

So why does gay-for-you bug me so much? It has got a bit of a “magic fix” tone to it that many queerfolk will find too close-to-home.

I know I’ve received the same message as an attack. Deconstructed, what gay-for-you often reads like is this: He’s a straight guy until the right gay fellow comes along, and then—libido engaged, and praise the magic penis!—eventually willing to go for the guy. They struggle, they win, they end up together. The end.

As a queer guy, you better believe that I’ve had some pretty hateful people tell me I just needed the right woman to come along to set me straight.

How much do you think a story like that would fly? A gay guy who meets a woman, and for the first time feels sexual attraction for a woman, and they get together, the end. No mention of bisexuality or a sexuality spectrum and no labels in play.

What about a lesbian who ends up with the first man who ever arouses her desires. Same scenario, no hint of any label other than she being a lesbian who goes straight-for-him.

As a queer fellow, the lack of discussion and labels and bi-inclusivity in sort of narrative makes me very nervous. Put the bisexuality back in there, and the queer nature of the relationships hold truer to life, and it doesn’t come across like some sort of dark “cure” story. Heck, you can even explore how much crap the bi characters endure from within the queer community. How novel would that be to see?

But hey, maybe I’m prejudging, and a “turns out he’s found the one woman who means he can call himself straight” story might do well and no one would mind, but I’m doubtful, and as a gay fellow, I can and do see the harm that narrative projects.

And even if it turns out the character does end up realizing their attraction to different gender partners in the past isn’t the same as what they’re feeling now, and they do come to realize they are gay or lesbian rather than bisexual or pansexual—this happens, yes, and nowhere here am I saying it doesn’t—you can still have that journey without erasing even the possibility of bisexuality/pansexuality in the process. It’s when there are discussions or dialogs around attractions to multiple genders at play and the words never appear that this erasure is at its worst.

But it’s my fictional character and I can do whatever I want…

So here’s the part that comes up in almost every post I’ve seen. “Ultimately, it’s fiction, so who cares? It’s made up and that’s how I see the character.”

Okay. You’re right. You totally can.

And people can give you feedback for poor portrayal of real-world, living-breathing cultures.

Here’s where we go back to the start of this post where I talk about how criticism—when done well—isn’t an attack.

I once had a really uncomfortable conversation, face-to-face, with an author I really admired. I love her books. Her mystery series is brilliant, and I was so excited to see meet her for the first time. And when I met her, I was very, very careful to mention first how much I loved her books, because I also had some criticism for her. The criticism was this: “Every gay couple you’ve introduced has had one or the other murdered before the end of the book.” Now, it’s a mystery series, right? Bodies will pile up. Some of the main character’s romantic partners have died, too, over the course of some of the books. And there are obviously not-gay characters aplenty who live and breathe and have romantic partners throughout the series who also lose someone. It’s a mystery series. But as a gay guy, I couldn’t help but notice the gay characters more, and there wasn’t a single couple who survived the length of a single book. If she introduced a gay couple, I knew one was going to be the murder victim. Every. Single. Time.

That was a problem. Whether intentional or not, even just from the basic point of view of giving your reader a mystery to chew on, she had a pattern she didn’t realize that showed her hand before she intended. Toss in the unintentional message, too—gay folk don’t get (or deserve) happiness—and it becomes something more problematic. And that message is one we queerfolk get loud and clear. You don’t have to go far to look at how queer characters are portrayed, so when you write a happy ending and then remove the bisexuality or pansexuality from it, what are you saying, exactly?

These same problems come time and time again across all forms of fiction. The black guy who self-sacrifices to save the white hero. The girl who has sex and then gets killed. The person with a disability who reminds the main character that their life isn’t so bad after all. There are tonnes of these, and they deserve criticism.

I can like the author, and her books, and still politely ask her why she thinks her gay folks never got to be happy. Luckily, she took the feedback incredibly well. She apologized and was embarrassed—which was absolutely not the point and not the end result I was looking for—but since then there are gay characters who are couples who survive from book to book—which was what I’d hoped I might accomplish: adding perspective.

I’ve also been on the receiving end of this kind of discussion. I’ve screwed up, and people have called me on it. It’s never fun. But I try to stop and listen. If the people upset are the real voice counterpart of a character I’ve written? I need to stop, disengage my defensiveness and possessiveness of “my” character, and listen.

I might still disagree. But I need to listen first, and really, really stop and think. The vast majority of the time, I learn, and vow not to make the same mistake next time. Next time, I try to do better. That’s all I can do.

When the first reaction to criticism is “I don’t see that,” it seems to me the first question on the part of the author (or disagreeing reader) should be “Why don’t I see that?”

I’m willing to bet that very often the answer is “I haven’t lived that.”

Rather than a declaration of opposition to the criticism, and dismissing it out of hand, it’s worth parsing. Every writer has gotten edits or criticism they’ve chosen to ignore. But a good writer knows even those ignored edits or criticism have value, and might point out something worth clarifying or exploring more. If an author didn’t intend harm, but harm is perceived, there’s likely an opportunity to clarify the message to reduce that accidental harm.

But seriously, it’s fiction. I’m not being political!

If you’re choosing to write about queer people, though, the thing is? You are.

Or at the very least, you’re kind of a teacher to your readers. You might not want to be, but you are. I can draw another parallel here, with a turn of phrase I used to see quite a bit in m/m fiction: “I’m clean.”

When I see it, I assume the author doesn’t know the following:

This phrase was absolutely used in the queer community, too. Some still do. It was a shorthand for saying, “I’m HIV negative,” (or, wider, “I have no STDs.”) But the reality was, it had a value judgement attached. Because what’s the opposite of clean? People who are HIV positive? They’re not dirty. There’s a major movement doing amazing and important work in ending the stigma of HIV/AIDS. It’s important in no small part due to how that stigma stops people from being tested, stops them from learning their status, and does lasting harm.

Years ago, I learned of this movement and I stopped using “clean” in my vernacular, and when I hear someone else using it, I point it out. The language used, and the behaviour the language can create, is important.

Now, when I’m at conferences or discussion groups, I’ll bring up the “I’m clean” as a line of dialog to avoid. It’s a teachable moment, it’s important, and it’s something people aren’t going to know unless they’re taught, right? After all, that’s how I found out.

The people telling me this information were the people affected by it. The caregivers, experts and activists, and people living with HIV and AIDS.

So, while I hadn’t used the phrase in anything I’d written, I now knew not to.

If I chose to do so again, I’m doing exactly that: choosing. I’m choosing to pass on something I know has the potential to be harmful.

When you write about queer characters, you have that same potential. And when those who belong to the group you’re writing about tell you in no uncertain terms that they feel harm by a message you’ve delivered, you can’t unknow that. If you keep doing it, you’ve chosen to do so. This works inclusively and exclusively. If you never have a character who isn’t white, or all the trans characters you write are always killed, or the person who uses a wheelchair is a prop to remind your main character her life could be worse, you’re propagating a problem. And you know it. And you’re choosing to do so.

And that’s totally within your right to do so as an author. No one will deny that. I certainly won’t. And I’ve heard authors bemoan that they’re just trying to write fun sexy romantic stories for their readers, and that we queer folk shouldn’t ruin their fun. But if an author chooses to put their reader’s fun over active harm their portrayal of queer characters does, then they’re going to get called out on it.

Don’t be surprised if people point it out, and don’t feel slighted if others don’t suggest your work because of it, or let others know the content included should be avoided by those who aren’t looking for one more reminder of how they’re not worth inclusion.

The difference with the gay thing…

One thing those of you who’ve heard me talk about queerdom over and over again have definitely heard me say before is my usual riff on how queer culture isn’t inherited. It bears repeating. We queer folk don’t inherit our narratives, and our lineages aren’t clear and certainly aren’t taught in mainstream history classes.

What I mean is, we almost never have lesbian daughters being taught about their trans grandparents by their bisexual mothers and gay fathers. We have to go find our history and we often grow up in a home that assumes we are something else until we say so. Coming out is a part of the process (and a process, by the way, that never actually ends. I’m forty-one, married to my husband, and every time I mention him in public with people I’m meeting for the first time? That’s coming out, with all the inherent risks thereof. Again. And again. And again.)

For many of us young queerlings, fiction was the first place we learned anything about ourselves. My first gay anything was a character in a book. My stunned realization about that character was only matched by the horror of that character’s miserable death, presented as an “of course he died, he was gay.”

Think about that for a second: what if the only time you saw yourself represented in the media around you, it was negatively. Or, worse, you just never saw yourself at all. That has impact. It has massive impact. We need the Uhuras and the Ellens and the Kurt Hummels and the Dr. Houses and the RuPauls and as many stories and representations as we can have that show us futures that include people like us.

But tell me what you really think…

Okay. This is way too long and way too wordy and I’m sure I’ll never be happy with what I’ve said or how I’ve said it.

Shortest form possible?

It’s totally possible for a reader to enjoy something and love something and for it still to be something that harms others. If the living and breathing actual real-life counterparts of a group an author is choosing to write about are saying the portrayal of people like them is off, then the author should stop and listen.

Shorter than that?

When an ally doesn’t listen to the people they say they support, they’re not supporting them. They’re silencing them.

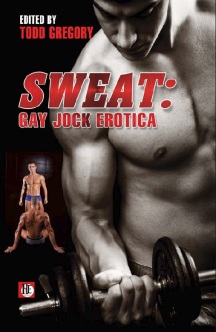

Was this helpful? If it was, I’m glad, as that’s always my hope with posts like these; but if you also feel like maybe tossing a buck or two my way, I do have a gay erotic short, Rear Admiral, and a wibbly-wobbly timey-wimey gay romance novella, In Memoriam you can nab.

Pingback: Pseudonyms vs. Identities | 'Nathan Burgoine

Pingback: Short Stories 366:218 — “Caught Looking,” by Adriana Herrera | 'Nathan Burgoine

Pingback: Short Stories 366:282 — “Seb and Duncan and the Sirens,” by Alex Jeffers | 'Nathan Burgoine

Pingback: The Shoulder Check Problem | 'Nathan Burgoine

How on earth did I miss this one? Seriously, you are my go-to when I can’t articulate these things properly without becoming apoplectic. I love you and your wisdom, Mister Apostrophen. Thank you for having the patience and grey matter to say what’s important. You’ve definitely pulled me up by my bootstraps, too. I was blissfully unaware I only wrote books about gay men, and your voice was in the back of my head constantly when I started introducing lesbian and bisexual characters. The name of the article you wrote which slapped me in the face escapes me right now, but I’ll find it again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ohmigosh, thank you!

LikeLike